The Dream of the Old Proctor Lynching Tree

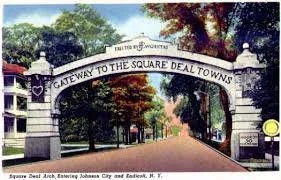

Russellville, Kentucky

——————————————

Listen, I will tell of a terrible dream

that came to me in the crux of the night.

The air was still as a sealed tomb,

heavy with drench-heat, thick with dread.

A deep-throated moaning moved through trees,

serpent agile, sharp as a spear.

Sweltering anger in anguished swirling

flooded the space between star and field.

I looked to see the source of the sound,

thinking to find such roiling thrum

coming from a crowded company;

instead the lament, in its manifold layers,

strenuously issued from one three-trunked cedar,

gnarled and poor on the old Proctor knoll,

crying out to a quiet heaven

and this is the tale it mournfully told:

“My birthright was to be a life-bearer,

to wave my green as a guarantor of hope.

A lightning tragedy turned my trunk triplet–

made me poster of the Person-Three God.

In this I was life-sign, a witness to love.

How then followed such a grievous foul-curse–

fated to harbor the hanging of men?

O, the first was a scoundrel, I freely confess,

Archie Proctor, proud on the drink,

murdered a Crafton in a cold-blood stabbing.

An angry mob impatient for action

stole the prisoner from the nest of his cell

along with his father in the chaotic flurry,

and soon saw the duo dangling beneath me;

the crowd crying “justice!”, smug to be judge.

It is not for these my night-howls seethe

and interrupt so rudely your sleep.

No, my indignation insists

on bringing to light a worse violation

in the rolling valley of Russellville

where John, Virgil, Joe, and John

were mob-murdered without mercy

by a crude posse of law-imposters

who lynched them on my begrudging limbs.

The fatal affair began with a feud.

Rufus Bowder, a black day-laborer

fought and killed Mr. James Cunningham,

wealthy landowner, white and connected,

when their disagreement turned into duel.

Cunningham swung a hitch-ring to silence

Bowder, knocked over, groping for balance,

both pulled pistols, both fired point-blank,

both men struck by the bullet of the other.

The white man dies. The wrong man survives

and goes into hiding. Grim were the days

after the War, the white presumed innocent,

the black figured guilty before asking facts

to illumine the story wherever it would lead.

Rufus Bowder was marked with a bullseye

and a lynching-fever spread like fire.

Sheriff Rhea arrested Rufus

and sent him to hide in the cemetery,

and then on a train to another town

to save him from the search party

frothing into a lynch feeding-frenzy.

The conflagration of rage and gall

roared unchecked into the jailhouse.

Four unfortunate men with flimsy

charges brooding ill-time behind bars

became the scapegoats, powerless, scared,

rough-handled, led to be lynched on me.

John Boyer, brother-in-law,

had helped Rufus during his hiding,

bringing him updates, being his eyes.

For this kindness, now called a crime,

he was deemed worthy of death.

John Jones cared enough to come

over to town on the afternoon train

when he’d heard talk of Rufus’ trouble

joining his brother, Virgil Jones,

around the table of the True Reformers,

a mutual help society that met

and reaffirmed support for Rufus

declaring the facts to prove self-defense,

and raising cash to help the case.

For daring solidarity

they were deemed worthy of death.

Tippler Joe Riley had no tie

to the unfolding Bowder affair.

Joe had landed drunk in jail

having fired a gun without forethought

in the open air outside a bar.

Wrong place, wretched timing,

he was deemed worthy of death.

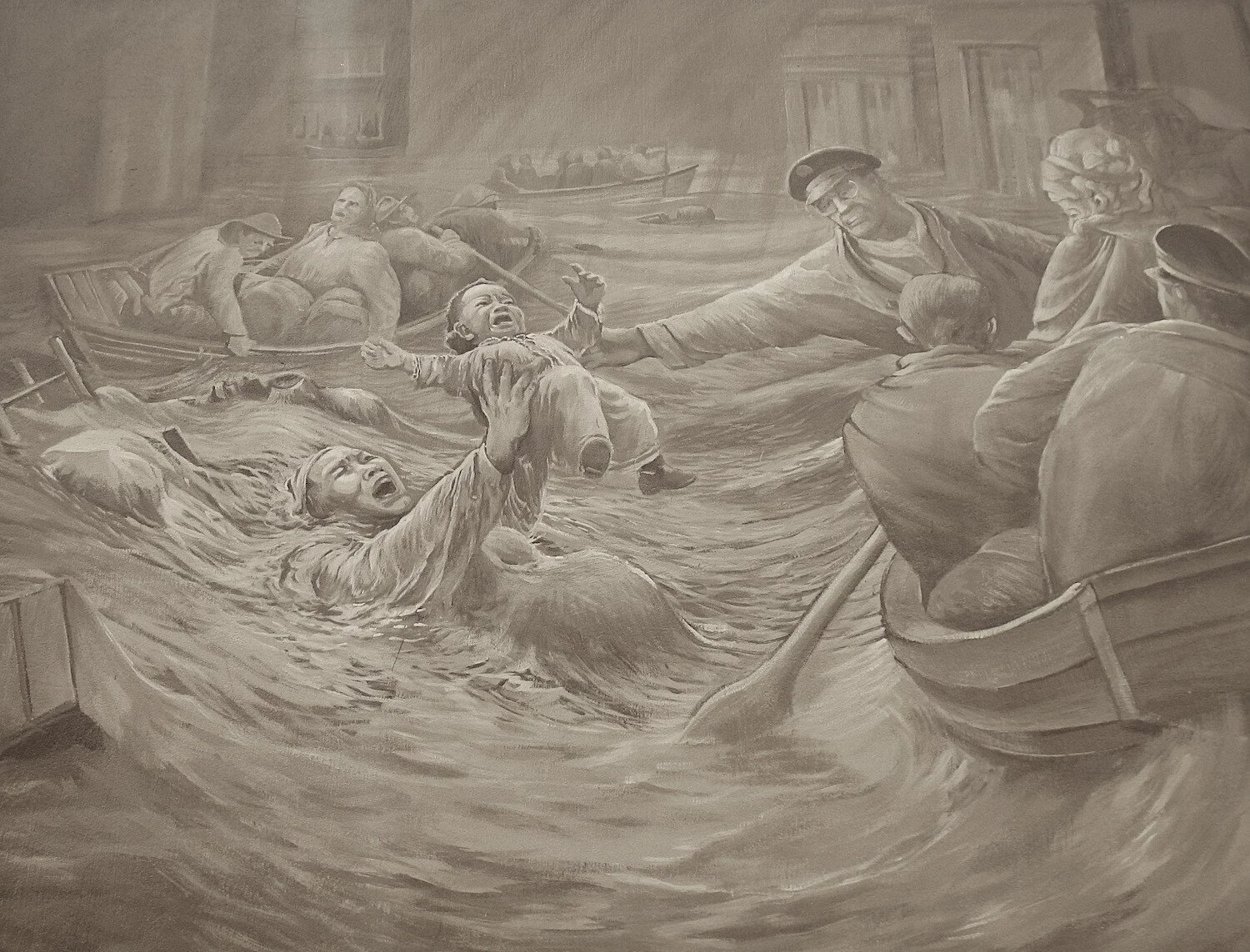

With hands bound behind their backs,

the four were led to the lynching tree

like Jesus carrying the beam of his cross

forced to march to the menacing skull.

At my feet, with fearful eyes,

buffeted by the brutal mob,

four men without hope in the world,

looked at each other, then up at me,

up at silent heaven’s stare,

down at the ground in grave despair.

If I could have cut myself

down that moment, I would have done it–

anything to rob the thieves

of their foul satisfaction.

But I remained immobilized

and rued the limits of the real,

arms outstretched to hold their string.

They took Joe first. The others forced

to watch the noose strangle his neck,

to watch the horror of his writhing

until the merciful moment of death.

John Boyer followed. Jones brothers wincing

at the macabre brazen killing.

Such unthinkable sick theater:

Virgil sees his brother seized,

noose slipped round the neck he loved,

the vicious heave, revolting snap,

vibrant eyes flickering to vacant.

Virgil erupted in a violent outburst,

and O so briefly broke away,

began to kick and bite and flail

until they knocked him to the ground

and wrapped a rope around his neck,

dragged him back below the branch

picked for him on which to be hoisted,

the last to suffer and suffering the most.

On him they pinned a hasty placard

warning others the unwritten order

still remained intact despite

the tantalizing promises leaching

out of the wounds of still raw war.

A camera snapshot became a postcard

leaving me immortalized.

Rufus’ fate was fixed in the law-court;

three trials later, the verdict was life

in prison. The Governor granted reprieve,

commuted his sentence to ten years served.

Rufus returned to Russellville,

his family waiting to welcome him home,

he came by railroad, but dead in his coffin,

tuberculosis having taken his life

(or so it was the authorities said)

to seal the tragic saga with sorrow

on sorrow–save one small thing to console me:

Rufus would never know the noose.”

I awoke relieved this revelation

was nothing but a nightmare terror.

The morning air was absent birdsong,

scattered clouds, the morning sun

filtered through the frightened branches

of the weeping willow at my window

painfully scratching at the pane

as if to tell me, as if it knew

this dreadful tale of its distant kin

was more than dream, more than the dark

could ever hold back of what had been.